The word “phoneme” gets tossed around a lot in talk of early reading instruction. It is an important concept in relation to phonics-based approaches to the subject. Reading teachers are typically taught that a phoneme is a “speech sound”,1 but that isn’t quite right. In fact, a phoneme is better defined as a set of speech sounds. So, a phoneme is a mental abstraction, a category. It is not an individual sound, but rather a collection of speech sounds that behave similarly. Individual speech sounds are called phones. These phones belong to a specific set, or category, of sounds,2 and it is the collection of sounds that makes up the phoneme. How does this work, then?

Let’s start by considering the ell sound as it occurs in the words “like” /laɪk/ and “milk” /mɪlk/.3 Speakers of English perceive the ell sounds in these words as being the same, but in fact they are systematically different. We are conditioned to treat them as being the same sound because they belong to the same phoneme, but with a little effort we can tease out their differences. So, let’s play with speech sounds.

First, say the word “like” out loud several times in a row. If you pay attention to the placement of your tongue tip while producing the ell sound, you will notice that it is in firm contact with the ridge of gum behind your top front teeth (it’s called the alveolar ridge). You can get that same ell phone by saying “lalalalala” rapidly. You will notice the repeated contact of your tongue tip with the alveolar ridge. This is the characteristic tongue movement we use to produce that specific ell phone; a specific instance of a phoneme is called a phone. We’re going to call this particular ell phone the light ell. This is the ell sound that occurs before vowels.

Now, let’s look at the word “milk”. Again, speak the word several times in a row with row. If you pay attention to your tongue position during the ell sound, you will notice that your tongue tip is not so firmly drawn to the alveolar ridge, if it touches it at all. In fact, the main tongue movement for the ell in milk is for the back of the tongue to raise up until it comes in contact with the soft palate (the rear part of the roof of your mouth). We will call this alternative ell sound (phone) the dark ell. You can pull off the same trick as with “lalala” for the light ell, by repeating the word “call” several times in a row with no breaks in between. The dark ell is the ell phone that typically occurs after vowels. (It’s not quite that simple, but close enough for present purposes.)

The light ell of “like” and the dark ell of “milk” are noticeably different speech sounds and they are produced with different, although similar, tongue movements. You can, if you choose, easily pronounce the word “milk”, or “call”, while keeping the tip of your tongue tucked firmly behind your bottom front teeth, to keep your tongue tip from touching the alveolar ridge. But if you try the same thing with the word “like”, its ell sound will be noticeably defective. (Go ahead. Give it a try.) The light ell and the dark ell are different phones (different speech sounds), but English speakers treat them as belonging to the same category of speech sound, the same phoneme. They are both ells.

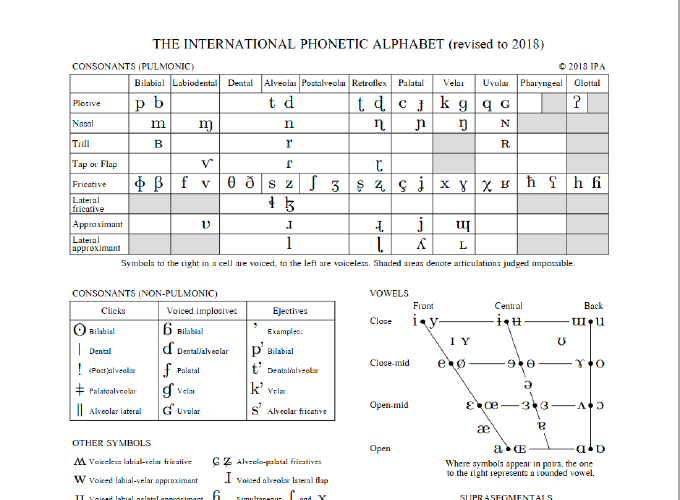

In fact, when the need arises, linguists will use a more detailed transcription to represent the phones that occur in a word, instead of the phonemes. This is called phonetic transcription and these are placed between square brackets, instead of slashes, to set them apart from phonemic transcriptions. Each phonetic variant of a phoneme will be represented by a different symbol. So, while the phonemic transcription of “milk” is as given above (“/mɪlk/“), the phonetic transcription looks like this: [mɪʟk]. Notice that in the first case, we use the same symbol (/l/) as for the ell in “like”. That’s because we have the same phoneme in both words. But in the second case, we use a different symbol ([ʟ]). In this case we are representing the specific phone (not phoneme!), which is different than the ell phone that occurs in “like”.

So what about the short-hand of calling a phoneme a speech sound? Does it matter if we gloss over what some might consider a niggling detail of little relevance? Certainly, in speech, a phoneme has to make its presence known somehow. So, it will be represented by a contextually appropriate phone. In hearing speech, it’s usually easy to relate each phone that you hear to the right phoneme. Exceptions can arise for a number of reasons, some more interesting than others. A few of the more common include: noise in the environment, inattention on the part of the listener, speaker’s accent unfamiliar to listener, and so on.

That said, there are at least a couple of reasons that phone–phoneme mappings may be of particular relevance in the classroom. First, the alphabetic principle at the core of the English writing system is a mapping between phonemes and letters. That’s why our spelling system maps light ell and dark ell to the same letter. Beginning readers may go through a phase where they try to map letters to phones instead of phonemes, and that can make for some creative spellings. A reading teacher needs to be able to recognize that that’s what is happening and help the student through it. Another issue is that, in different dialects of English, each phoneme may consist of different sets of phones. For example, speakers of some varieties of English may, instead of the dark ell, use a vowel sound (phone) as the variant of the ell phoneme that occurs after vowels. An example would be a pronunciation of “milk” as [mɪʊk]. The teacher should be able to recognize that this vowel phone is still a part of the ell phoneme, and instruct accordingly.

In this post, I’ve tried to shed light on the nature of phonemes and their relationship to speech sounds (phones), and to touch on why it can matter in teaching reading. Certainly, much more can be said, about phonemes and about the connection of speech to reading. I’ll follow up on both these things in later blog posts.

For example, Louisa Moats writes, “From a finite set of speech sounds (phonemes), speakers of an oral language say and understand many thousands of words” (p3).

Moats, L. C. (2000). Speech to Print: language essentials for teachers. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

[BACK]Actually, there are a couple of complications here that we’ll put aside for another day. The first is that the mental representation of a phoneme includes information not only about its perceptual properties (sounds), but also about the speech gestures (vocal tract movements) required to produce it. Second, an individual phone (sound/gesture) can belong to more than one phoneme!

[BACK]I’ll follow the linguistic convention of putting phonemic transcriptions between forward slashes.

[BACK]